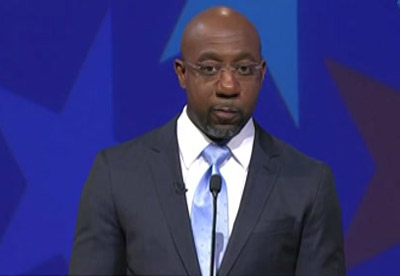

Warnock had called democracy a “political enactment of a spiritual idea, that we are all children of God, and therefore we all ought to have a voice in the direction of our country and our destiny within it.” In July, 2021, Warnock delivered a speech in the Senate chamber about voting rights which moved his colleague Senator Cory Booker, of New Jersey, to tears. But he has shown an ability to strike notes that Democrats have not struck for a very long time. Warnock is still relatively new to politics, having won his first campaign, in January, 2021, to fill the last two years of a Senate term, and he now holds only a slight lead in a reëlection campaign that he still may lose. What I’m trying to say to you is I’m not in love with politics. “It is that work that got me here in the first place. I’m used to standing there marrying couples, and speaking words of comfort when a loved one is sick, or standing there in some damp cemetery having to say farewell.” The gospel “compels us to speak on behalf of the marginalized members of the human family,” Warnock continued. I’m used to standing there with parents as they bless their babies. “I’m used to walking with people when they are in their lows and in their highs. Since 2005, he has occupied the pulpit at Ebenezer Baptist Church, in Atlanta, where Martin Luther King, Jr., was baptized and where he preached until his death, in 1968.

“I’m a pastor,” Warnock went on, once everyone had settled in. Warnock had mentioned the oak tree largely to fill time. There was an audible shuffling of chairs the audience members were still taking their seats. One of the speakers who introduced Warnock, the state representative Al Williams, had marched at Selma. During segregation, the school was for Black students only and had also served as a training center for civil-rights activists, where “they taught you what to do when they set the dogs on you,” as a rally attendee, a retired soldier named Gil, described it to me.

Warnock was standing on the steps of Dorchester Academy. It was nearing dusk, and the sky was lit in pink and orange. Recently, at a campaign rally in rural Midway, Georgia, Raphael Warnock took note of a magnificent oak tree “with Spanish moss,” he said, “bending and beckoning the lover of history and horticulture to this magic place.” Even so, when an orator presents himself, it tends to attract attention. The number of politicians who have an ornate twenty-five-minute speech prepared about the arc of the American experience vastly exceeds the number who will ever deliver one.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)